SHARE

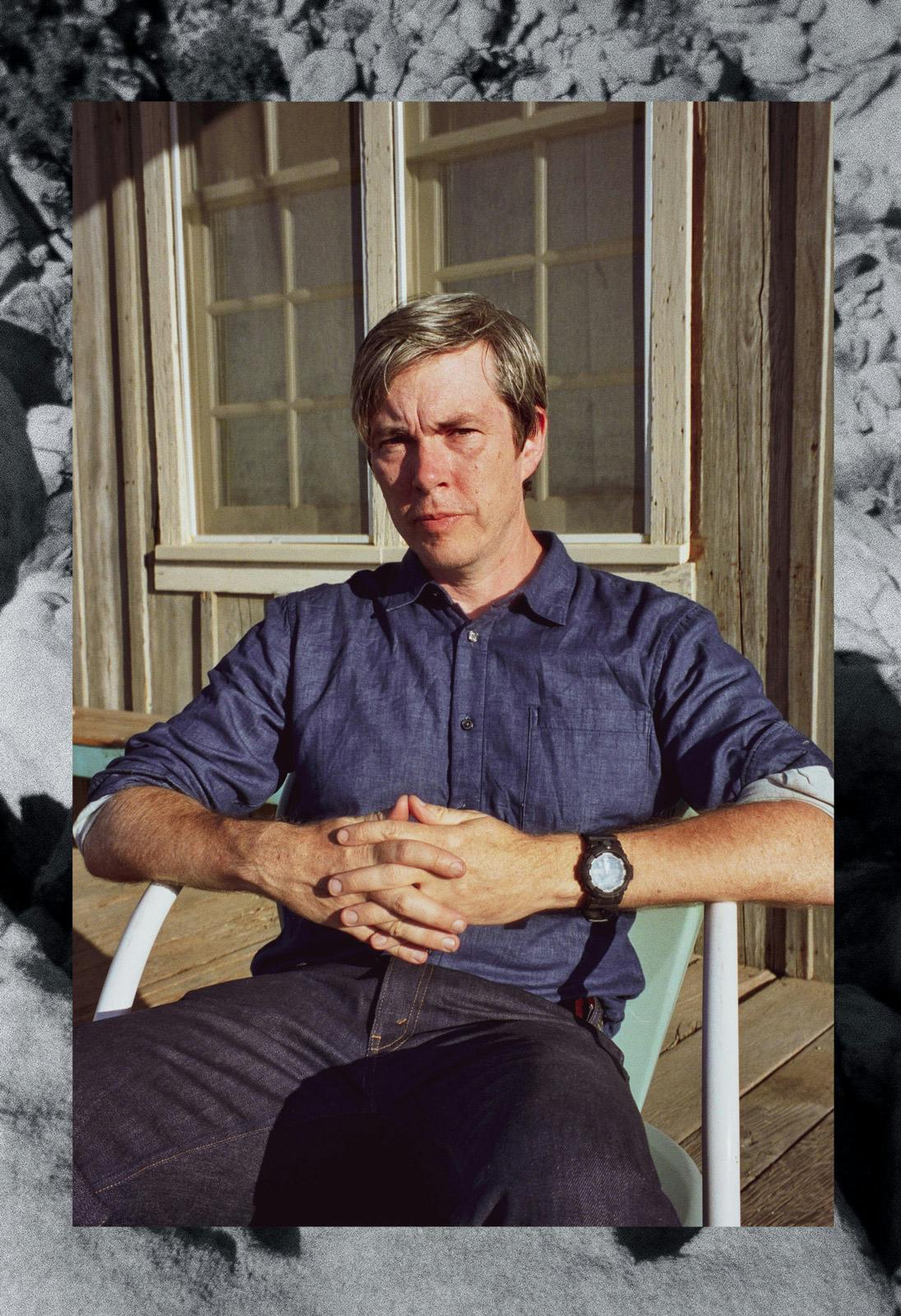

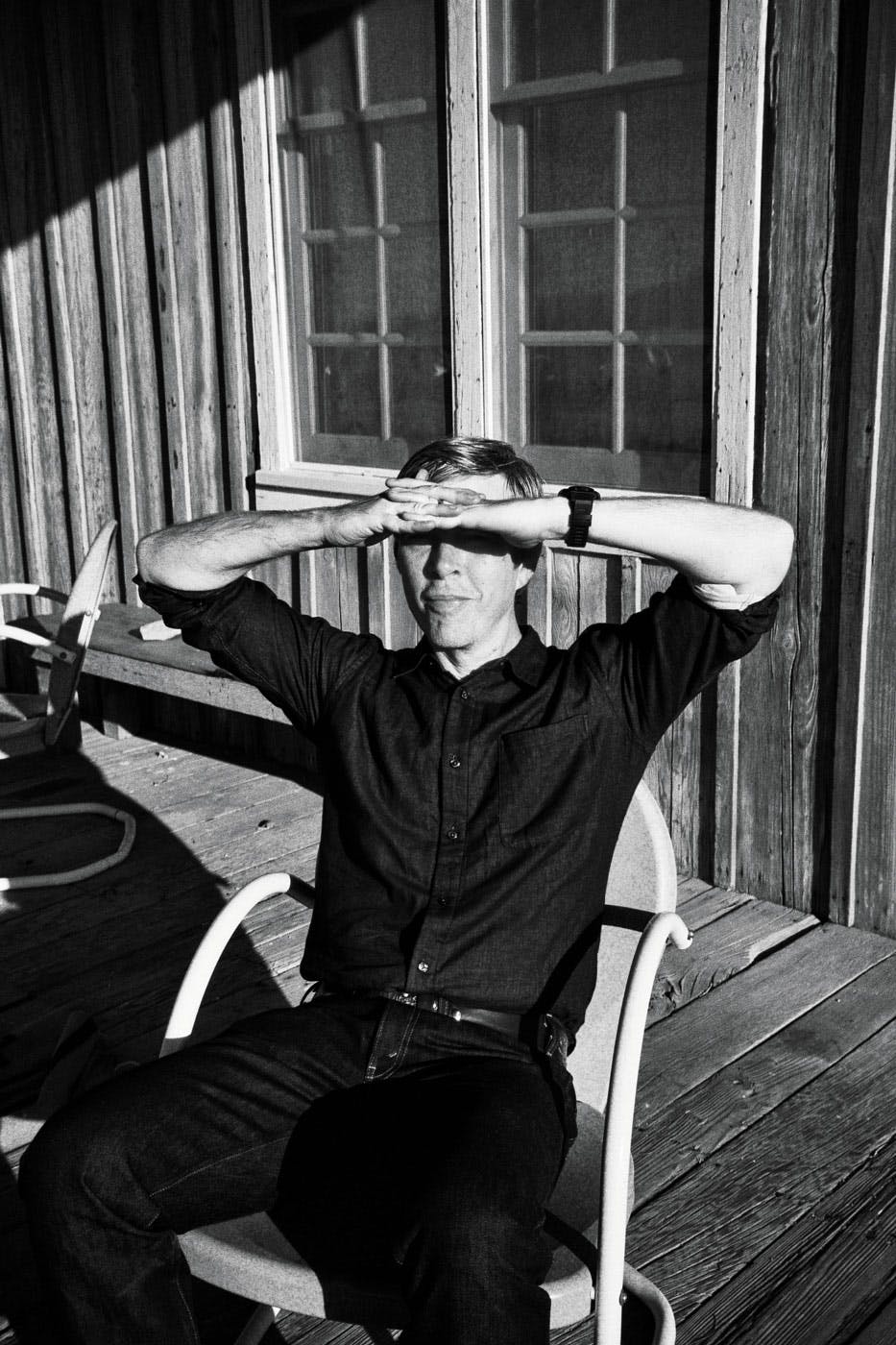

Bill Callahan

With the long-awaited release of Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, has Bill Callahan changed? Or does the song remain the same?

|

Music

Photographed by Caitlin Dennis

Certain musicians are beloved more as writers than performers. They craft songs that reward squinting at the liner notes, and repeated listens alone in your car, driving aimlessly at night along dark country roads, where the particular significance a song has to you can grow and morph as you age with it.

Among this class, Bill Callahan may reign supreme.

Fans of the reticent bard have, until recently, been disappointed in the quality and quantity of the interviews he’s submitted himself to. In a particularly painful 2011 New York Times interview, the writer met Callahan in a midtown Manhattan cafeteria in the dead of night and found it like “pulling teeth blindfolded” to get him to answer questions. In the last few months, however, not only has there been a spate of meaty profiles done on the songwriter, but within them he is forthcoming. To evolve from, “I’m trying to be more… Yeah, just more, universal, or something,” to “I used to just have music on my plate. Now there’s more, so it’s like, how do I eat all of this?” (The Fader, 2019) is a pretty big leap.

The occasion for this plethora of press is his newest album, Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, released in its entirety on June 14, 2019. The album is his first since 2013’s critically-lauded Dream River, which was itself a turning point for Callahan, employing a spare musical arrangement to showcase his sonorous vocals and bone-dry humor.

Six years is a long time. Dedicated Callahan fans had all but given up hope until last winter, when Drag City tweeted: “It’s a holiday miracle, Bill Callahan has joined Twitter! Follow him at @BillCallaman and receive a special surprise on 12/24!” That announcement, funny spelling and all, turned out to be a little delayed. In early May of this year Callahan finally let it drop that he was putting out a double album, which was released on streaming platforms one side per week until the full album’s release.

The reason behind Shepherd’s excessive delay: life. In 2014, Callahan and documentarian Hanly Banks married and relocated permanently to Austin, Texas. Their son Bass was born in 2015; shortly thereafter, Callahan’s mother fell ill and passed away.

Now 53, Callahan acknowledges that he thought about throwing in the towel during that time. When we speak on the phone, between legs of his tour for Shepherd,I ask if he worried, as so many artists do, whether the muse had left him. “No, it’s like it wanted to get out,” he tells me in his molasses-drip voice. “I knew that there was something trying to converse with me, but I didn’t know how to converse with it yet because so much of my life had changed.”

Any way you cut it, Callahan’s nearly 30-year career is impressive, and especially so when you look at the numbers. He released his first album, Sewn to the Sky, in 1990 under the name Smog. That project (Smog) started with Disaster, a fanzine that Callahan put out briefly, and several homemade cassette tapes of his music that were mailed out to fans who placed orders through the ’zine. In 1991, he was signed to the Chicago-based label Drag City, and has been with them ever since, through 12 albums ending with 2005’s A River Ain’t Too Much To Love and continuing with 2007’s Woke On A Whaleheart, his first album under his birth name. Counting the five after that, Callahan has released 22 albums over his lifetime, many of them masterful. Each tells its own story: “I tend to start each record as if it was the first record,” he explains. “Everything from scratch and what I feel like doing at that particular moment, the kinds of sounds that I want, it’s all based on that moment in my life, at the beginning of the process.”

Despite his music’s country-tendencies, Callahan hails from the eastern seaboard. Both his parents worked for the NSA doing language analysis and code breaking, and the family moved around a lot when he was growing up. He has characterized the family relationship as cold, saying, heartbreakingly, in a recent interview with Pitchfork that his father told him recently: “I didn’t really care about any of you kids. I was just focused on myself and my career.” Among other major life developments over the past six years, his mother passed away after moving to Austin to be closer to him, his wife, and their young son. In that same interview, Callahan recounts: “As she was getting older, I begged her: Show your children who you are, because we want to know before you die. She couldn’t do it. So now she’s still just an unfinished person for me.”

In as much as you can track an artist’s life and state of mind by their art, Callahan lays it out there pretty solidly on Shepherd. The experience of being with his mother in her final hours found itself onto the album, along with many others from the last six years, in the song “Circles” “I made a circle, I guess / When I folded her hands across her chest.” In “What Comes After Certainty” he discusses the joys that come after finding and marrying the love of his life: “Well, I never thought I’d make it this far / Little old house, recent-model car.” In “Tugboats and Tumbleweeds” Callahan lays out some life advice for young Bass: “Some time alone when you are young is good / High, high time, and drunk old time, sober time / I advise all three when your brain is at least twenty-three.”

According to Callahan, releasing the new album one side a week—each side comprising five songs—had less to do with the length of the album and more to do with the way most of us consume music now. “I know from my own experience with streaming that’s really tempting to—even if you’re enjoying the song—wonder what’s next and skip through it,” he says. “So we wanted to sort of just roll the record out slowly so that some people will be excited by the kind of ‘chapter’ method of doling it out a little bit at a time. It might make it more memorable for the listener and easier than asking someone to sit in front of their computer for 20 songs that they’ve never heard. Five at a time is a little more manageable.”

Does Callahan’s consideration of his music’s end-point influence the song-crafting process? “To the extent of trying to make a narrative with the sequence of the album,” he says. “Especially with the Side One songs on this record, I found that because they’re so short and compact that it’s hard to maintain my own attention span to get through them that I added a transitional moment—on Side One, at least—between every song so that they each kind of fall into the other one. So I make considerations like that, for how the listener is going to feel.”

To my surprise, over the course of writing songs for 30-odd years, “Nothing changed at all. I feel the same as when I was 19 or 20 and I was making my first album, writing lyrics that I liked and bringing in the music and recording it all. It’s a feeling that doesn’t change. It’s like other bodily functions, it doesn’t change no matter how many times you’ve done it.”

Listening to Shepherd, there are a few lyrics that stick out as bellwethers of Callahan’s personal worldview. In “What Comes After Certainty” he sings, “I don’t believe in faith, I believe in destiny.” I ask Callahan what the differences are between those two concepts for him: “Well, I’d say faith is something that is thrust upon you, and destiny is something that you are headed toward, something you get for yourself, because it’s the way it’s supposed to be. One is dropped on you and the other you take.” He pauses for a long moment, adding, “I do believe that a lot of people’s lives are in their control as far as all the things that matter: their relationships, their health, and their social health. A lot of those things are in our control, and it’s dangerous to start thinking that something or someone else is working against you, even the universe; the universe doesn’t really care about you.”

“It’s dangerous to start thinking that something or someone else is working against you, even the universe; the universe doesn’t really care about you.”

In a 2011 interview with The Rumpus,Callahan said about performing, “You first need to knock down the city the audience has built while waiting for you. Because they don’t really want to be in that city they built; they just didn’t know what else to do with their minds while waiting. Then you build them a city.” Two albums and hundreds of shows in the meantime, his perspective has shifted. “Maybe it’s more like, not knocking it down, but just doing a little renovating,” he says. “I might have felt like I had to knock it down, but now I think it needs a few adjustments here and there. Some secret secret doors, secret rooms that people don’t know about.”

Since his early Smog days Callahan’s singing voice has gradually aged into a silky baritone and his musical arrangements have become less ornate and have evolved to showcase his vocals more. Has his relationship to it evolved, too? “I guess I feel like there was a point maybe around A River Ain’t Too Much to Love where I felt like I was finally singing in my real voice, which was a landmark time for me, I guess because, up until that point I mostly considered myself a record maker, or performer, so the vocal was never really approached as a performance type of thing. It was more like a part of a song, like a sound. Then, around 2004, I started desiring to make my singing more like a performance and the records more like performance things instead of collaged-together sounds. I just try to stay in touch with the voice that I found. So now my voice on the old records does not sound like me, but I think maybe I wasn’t me… and now I’m me.”

Try a cup on us

Order A Sample

SHARE